From Roderick Lawson’s book Places of Interest about Girvan, with Some Glimpses of Carrick History.

The page displayed in the eBook closely match the layout of the printed book. However the excerpt below may not manage to recreate that layout. The image watermarks are not present in the eBooks.

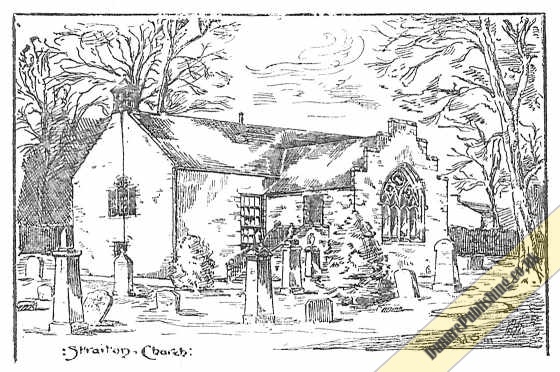

Straiton

THE Parish Church of Straiton is strangely composed of two portions. There is first the old aisle, built of hewn stone, with gothic window, and outside staircase. And then there is the modern white-washed portion, as plain and bald as may be. The old aisle formed part of the Roman Catholic Church which stood here before the Reformation, and shews the stress men then laid on beauty in church architecture. The modern barn-like building, with its square windows and rough-cast walls, shews the little taste and less cost our Protestant forefathers expended on the worship of God. In this way, Straiton Church is a standing parable regarding the two forms of faith. It is true the building is now purged of its crucifixes and images, and even the stone cross which once overtopped the gable of the aisle has been demolished. But piety need not be at war with beauty, neither does holiness necessarily consort with baldness. It is hoped the day is coming when we may yet count it a privilege to make the “House of God” as comely as our circumstances will allow.

In the Churchyard there are several notable memorials. The oldest stone, which lies immediately below the Gothic window, bears the following inscription:– “Here rests the bodie of Mr John M’Quorne, younger, in hope of the joyful resurrection. He died in peace, 1st May, 1612, aged 23. VIXI. VIVO MELIVS. OPTIME VIVAM.” (I have lived : I am living better · I shall yet live best of all). This young man was son of the second minister of Straiton, who was translated from Maybole to Straiton in 1598. His father, unfortunately, was afterwards deposed for drunkenness.

There is also a Martyr’s Stone, with the following lines upon it:—

“Here lies Thomas McHaffie, Martyr, 1686.

Though I was sick and like to die

Yet bloody Bruce did murder me,

Because I adhered in my station

To our Covenanted Reformation.

My blood for vengeance yet doth call

Upon Zion’s haters all.”

This Covenanter was son of the farmer at Largs, near the village. He had hid himself in a glen on the farm of Linfairn, but being seized with fever, and having taken refuge in a house near at hand, he was dragged out of his bed and shot on the road. The last two lines of the epitaph are somewhat bloodthirsty, but we must remember that they were written not by the martyr but by some versifier for him.

In this Churchyard are also buried several generations of the M’Cosh’s of Carskeoch, near Patna, whose family tree has blossomed in these modern days into Ex-President James M’Cosh, of Princeton College, New Jersey, United States. Some years ago, I remember having gone, by arrangement, to preach at Straiton, and found that the President was there, staying for a few days with his sister, the late Mrs M’Adam, of Dalmorton. He came into the vestry that morning, and asked leave to preach for me, as it was the last opportunity, he thought, he should have of preaching in the church of his boyhood. I, of course, consented, and he chose as the subject of his remarks those verses in the 16th chapter of John, which set forth the office and work of the Holy Spirit. At the conclusion, he spoke a few words about his early connection with Straiton Church, and pointed out the pew in which he used to sit. In those days, he said, the whole family were in the habit of walking every Sunday to church across the moor (4 miles), and returning after service. All the young lads of his own age whom he knew at that time were now dead, many of them having wasted their lives through strong drink. He had thought it right to leave the Church of Scotland, and even Scotland itself; but though living in America, he had still a warm side to his native land, his native parish, and the old church round which his fathers were resting, and he was glad to have this opportunity of saying these things within its walls.

After service, I was invited to dine with the President at the Manse. He was very pleasant and affable, dwelling much on old times and persons. I asked him how he liked the Americans, and mentioned that I had heard they used ministers there as they used oranges—suck all the juice out them, and then fling them away. He said it might be so in some cases, but they certainly had not so used him. If I might judge from what I heard that day, I should say that the President could never have been a pulpit orator, although there was a certain homely earnestness about his words which had their own effect But he had found his life-work in training students, and writing philosophical treatises—the most popular of these being the Method of the Divine government. In this way he has become a man of mark, a credit to Straiton, to Ayrshire, and to the Presbyterian Church generally. The oldest member of the M’Cosh family buried in Straiton Churchyard is Jasper M’Cosh, who died in 1729; and I remember the old President (now in his 81st year), when he came out of the church, went to look at the stone, told me it was the oldest record of his family he could trace, said he would never see it again, and then stooped down and affectionately patted the weather-worn memorial, as he took his final leave of it.